Co-authors discuss How China Became Capitalist

Video courtesy of Chicago Multimedia Initiatives Group

Video Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zWUycRtsuHs

Video by UChicago Creative

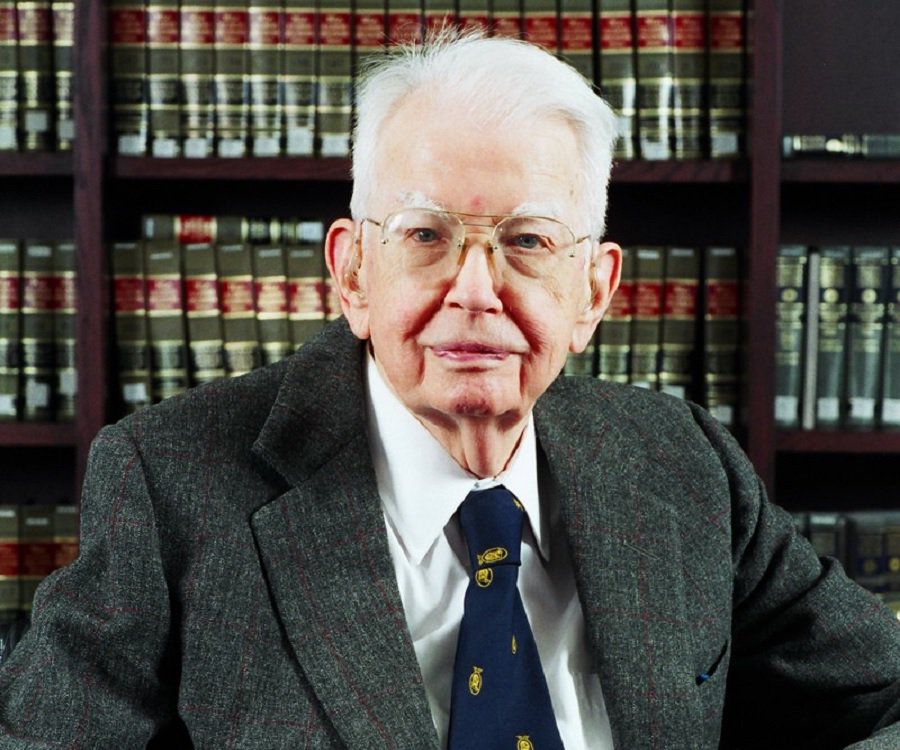

Ronald Coase still stirs debate at 101

Story by Sarah Galer

Main photo by Jason Smith

At 101 years old, renowned University of Chicago Law School economist Ronald H. Coase has never stopped generating new ideas or giving his witty, confident take on past intellectual skirmishes.

His latest ideas are in a new book that Coase co-wrote with Ning Wang, PhD’02, titled How China Became Capitalist. It is a fresh example of the intellectual approach that Coase first brought to the University as a visiting scholar more than half a century ago.

On that evening in 1960, Coase persuaded a room full of skeptical Chicago economists—including future Nobel laureates Milton Friedman and George Stigler—to take his point of view on an important question of law and economics. In the process of winning them over, Coase honed an economic theory that would later win him a Nobel Prize in 1991.

“They were very impressed that I had changed their views, but I wasn’t particularly impressed because all I was doing was stating the obvious,” recalls Coase, who joined the UChicago Law School faculty in 1964. He is now the Clifton R. Musser Professor Emeritus of Economics.

Celebrated for his groundbreaking work on the economics of the firm and in the area of law and economics—a field born at the UChicago Law School—Coase has turned his academic acumen to China, a country that fascinated him since he read about Marco Polo as a boy. His writing is finding eager audiences there, an indication of the far-reaching impact of Coase’s work.

“Anyone would be hard-pressed to find another economist that has shaped the direction of the field of law and economics as much as Prof. Coase,” says Wang, an assistant professor at Arizona State University’s School of Politics and Global Studies. “In China, Coase has profoundly influenced the way its market economy has evolved, particularly his emphasis on the delineation of property rights as the precondition for market transaction. He is probably the most well-known Western economist there.”

Seeking novel solutions

Coase often has upended widespread ideas about economic questions. That was the case in his 1960 talk, in which he argued that the incentives of private parties to resolve disputes in their own best interests, even if courts are involved, should result in an efficient, mutually beneficial solution that is always preferable to government intervention.

The workshop where Coase presented his views left a lasting impression on Stigler, PhD’38, who reminisced about it in his 1988 book, Memoirs of an Unregulated Economist:“In the course of two hours of argument, the vote went from 21 against and one for Coase to 21 for Coase. What an exhilarating event! I lamented afterward that we had not had the clairvoyance to tape it.”

Since the publication of “The Problem of Social Cost,” the article that resulted from that storied evening, other economists have applied its underlying idea, often called the Coase Theorem, to virtually every area of human activity. Notable recent applications of the idea have come in such issues as the sale of rights to broadcast on portions of the electromagnetic spectrum and the problem of pollution.

Coase himself disputes the origins and basis of the theorem, saying it is not actually based on his work, but was coined by Stigler.

“It is not about my work at all,” says Coase. “George Stigler, who was a very nice man, wanted to pay me a compliment so he invented the Coase Theorem, but he named it the Coase Theorem instead of the Stigler Theorem. He was being nice, but it was unfortunate.”

Coase says he took the position at the Law School to take over as editor of The Journal of Law and Economics, a position he held until 1982. “I used the journal to try to change views,” Coase says. “And I did it. It formed the field of law and economics.”

“It was the first law school, to my knowledge, that had an economist teaching full time,” said University Professor Gary Becker, the 1992 Nobel laureate in economics, at a luncheon in honor of Coase’s 100th birthday, according to The University of Chicago Magazine.

When Becker first met Coase in 1970, Coase “didn’t say a lot, but I began to realize that every time he did say something, it was really profound.”

“Little more than an undergraduate essay”

Coase was born in a suburb of London in December 1910, the only child of a Post Office telegraph operator and his wife. He studied at the London School of Economics, where he met Sir Arnold Plant, who introduced Coase to Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” and to the idea that competitive economic systems could be coordinated by the pricing system.

He says his first landmark paper, “The Nature of the Firm,” was “little more than an undergraduate essay.” It stemmed from a scholarship that let him spend a year studying the structure of American industry and the question of why some work was performed inside firms and some by the marketplace. He later came to dispute his own finding that firms have diminishing rates of return as they grow bigger. The growth is a sociological problem, Coase now believes, not an economic problem.

“Ronald belongs to an era before economics was taken over by mathematicians,” says Douglas Baird, the Harry A. Bigelow Distinguished Service Professor of Law. “He thinks about economics in intuitive terms. He does not think that there are any important terms in economics that you cannot understand using words, descriptions, and arithmetic.

“Some people say that shows he is from a much earlier era. The better view is that there is something fundamentally healthy about his work that is too often lost on modern economists, who are sometimes so enchanted by mathematical models that they lose touch with planet Earth.”

‘Finding new challenges’

How China Became Capitalist, Coase’s newest academic work, traces the market transformation China has experienced over the past 35 years. The book argues that the changes came not from deliberate actions taken by Chinese leadership, as often claimed by Beijing, but from “marginal revolutions.”

“China became capitalist while it was trying to modernize socialism,” write Coase and Wang. “The story of China is the quintessence of what Adam Ferguson called ‘the products of human action but not human design.’ A Chinese proverb puts it more poetically:‘The flowers planted on purpose do not blossom; the willows no one cared for have grown into big shade trees.’”

Coase already has set his sights on his next project, one that speaks to the intuitive side of his approach to economics. He plans to launch a journal entitled Man and the Economy, for which he will serve as founding editor.

“We are going to do again for economics what I did with law & economics:We are going to establish a subject,” Coase says. “Economics has become a theory and math-driven subject, and I believe the approach should be empirical. You study the system as it is, understand why it works the way it does, and consider what changes could be made in order to improve the system.”

Coase says his main scholarly talent has been to identify solutions that were in plain sight.

“I’ve never done anything that wasn’t obvious, and I didn’t know why other people didn’t do it,” he says. “I’ve never thought the things I did were so extraordinary.”

罗纳德·哈里·科斯(Ronald H. Coase)——新制度经济学的鼻祖,美国芝加哥大学教授、芝加哥经济学派代表人物之一,1991年诺贝尔经济学奖的获得者。

时年101岁的科斯指出:“过去三十年来,中国发生的令人瞩目的市场转型。然而,不是中国政府,而是我们称之为的“边缘革命”,将私人企业家和市场的力量带回中国。”

只要有自由竞争的环境,私企是非常懂得如何应对这些交易费用的。如今,私企最大的挑战是,他们仍然遭受着种类繁多的政策和政治歧视。他们很难进入资本市场,因为资本市场主要是由国有银行所控制。

设置的种种限制。只要私企(或任何企业)是依法运营,就该享有自由。如果一些经济行为体不遵守市场原则,市场经济就不会成功。必须去除所有加诸国企的特权,让私企得以自由竞争。

政府参与土地交易导致腐败猖獗,必须将其自身排除在市场之外

只要交易双方可以自由讨价还价并达成交易,那么市场行为就可以发生。中国的情况是,政府宣称了对土地的拥有权。国家必须允许土地的事实所有者——多数情况都是农民——进入市场。

这样,国家可以通过收税在土地交易中获得很大利益;同时,为了自身利益,就必须将其自身排除在市场之外。

国在土地交易方面的所作所为,应该叫做单方面获取。这显然并不是市场行为。

政府参与土地交易导致腐败猖獗,带来大量失去土地者的抵抗,这在中国已经被广泛报道。

打造一个自由的土地市场

(深圳发布了一个土地双轨制文件,允许深圳农村变卖集体所有的工业用地。你认为,这是否为中国土地政策提供了一个改革的方向?)

深圳的政策显然是朝着正确的方向前进。中国是一个辽阔而多元化的国家。一种方法或许在一个地方能取得成功,但在其他地方可能就行不通。中央政府应该鼓励地方政府大胆尝试不同方法,打造一个自由的土地市场。

不平等在任何自由市场经济中都不可避免。考虑到中国的庞大以及地区多样性,基尼系数高也在预料之中。争议的核心在于,导致不平等问题出现的中国市场经济,其深层问题是什么。

比如教育和税收制度,在最发达国家都发挥着强有力的抑制不平等的作用。在中国,两项制度都加重了不平等。只要社会流动的大门是打开的,处于社会结构底层的人对自己的未来、自己孩子的未来有希望,那么不平等本身就并不是问题。

计划生育政策显然需要反思

在发达国家,更替水平生育率被设置为,每位女性平均生育2.1个孩子。长远来看,独生子女政策并不可持续。另外,保证政策的实施过程,一向是高成本且充满暴力的。随着一个国家的富裕,女性也趋向于自愿降低生育率。今天没有必要来强制执行如此严苛的政策了。

独生子女政策不仅削弱了中国劳动力数量,还降低了其质量。研究已经表明,独生子女政策实行之后出生的中国儿童,其社会技能被迫变低。当然,其影响也在经济之外有所体现。它在基本社会结构上,也严重削弱了家庭。

过去三十年来,中国发生的令人瞩目的市场转型。然而,不是中国政府,而是我们称之为的“边缘革命”,将私人企业家和市场的力量带回中国。

饥荒中的农民发明了承包制;乡镇企业引进了农村工业化;个体户打开了城市私营经济之门;经济特区吸纳外商直接投资,开启劳动力市场。与国有企业相比,所有这些都是中国社会主义经济中的“边缘力量”。

我相信经济增长的秘诀是分工,研究分工就必须考察真实世界。过去半个世纪以来,我一直在呼吁我的同行们从黑板经济学回到真实世界。不过没有什么效果,我的同行们似乎不大愿意听我的劝告。中国有那么多优秀的年轻人,那么多优秀的经济学者,哪怕只有一少部分人去关心真实世界,去研究分工和生产的制度结构,就一定会改变经济学。我始终对中国寄予厚望!

让其政治权力服从于法治

人类社会到处都存在着腐败。过去50年间,我在芝加哥的家中,常常听到市政官员的腐败新闻。伊利诺伊州的两任州长现在都身陷牢狱。我的同胞、英国历史学家艾克顿公爵解释得很清楚:权力产生腐败,绝对的权力产生绝对的腐败。如果政治体制是透明的,如果权力由法律来约束,如果任何权力的滥用都可以追溯责任(自由媒体和独立司法体制,因而是需要的),那么腐败就不会威胁到秩序和稳定。

无论是政治改革、法制改革,还是体制重建,叫法无所谓,中国必须让其政治权力服从于法治。

开放思想市场

中国没有理由比韩国、日本或美国缺少创意。只要中国开放思想市场,允许大学独立、自治,给私企以与国企同等的待遇,中国就会迅速在科技方面更上一层楼。

中国已故的物理学家钱学森也许提示了一个耐人寻味的答案,在与温家宝总理会面时,钱学森提出了一个发人深省的问题,“为什么中国的大学在1949年后没有产生一个世界级的原创性思想家或有创见的科学家?”

钱学森之问帮我回答了中国读者向我提出的问题。而就钱先生的问题,我却有个答案,那是因为中国缺乏一个开放的思想市场。

中国的经验对全人类非常重要!

我是一个出生于1910年的老人,经历过两次世界大战和许多事情,深知中国前途远大,深知中国的奋斗就是全人类的奋斗!中国的经验对全人类非常重要!